| ABOUT DV | CONTACT | SUBMISSIONS |

What’s Wrong with the STRIVE Immigration Bill

by Justin Akers

Chacón

www.dissidentvoice.org

April 14, 2007

![]()

One year after the mass marches for immigrant rights that challenged repressive legislation proposed by congressional Republicans, the Bush administration is set to unveil harsh new proposals to supply Corporate America with cheap and vulnerable immigrant labor, ratchet up enforcement, and make it extremely difficult for undocumented workers to become U.S. citizens.

According to Ben Feller of the Associated Press, Bush’s plan “would grant work visas to undocumented immigrants, but require them to return home and pay hefty fines to become legal U.S. residents. They could apply for three-year work visas, dubbed ‘Z’ visas, which would be renewable indefinitely but cost $3,500 each time . . .

“The undocumented workers would have legal status with the visas, but to become legal permanent residents with a green card, they'd have to return to their home country, apply at a U.S. embassy or consulate to re-enter legally and pay a $10,000 fine. That's far more restrictive than the bipartisan bill the Senate approved last year.” The Bush proposals would break up of immigrant families, too, according to the Washington Post: “In a new twist, more green cards would be made available to skilled workers by limiting visas for parents, children and siblings of U.S. citizens. Temporary workers could not bring their families into the country.”

Many in the immigrant rights movement have looked to the new Democratic Congress to provide an alternative to Bush and the hardliners. Instead, the Democrats are seeking a compromise palatable to the ultra-conservatives in the Republican Party.

The result is a bill -- co-authored by two House members, liberal Democrat Luis Gutiérrez and conservative Republican Jeff Flake -- known as the Security Through Regularized Immigration and a Vibrant Economy, or STRIVE Act. It combines a guest-worker program with resuscitated elements from last year’s effort to criminalize undocumented workers led by Rep. James Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.)

Top-heavy with punitive measures, the STRIVE Act is designed to be an offer the right wing can’t refuse. That’s why it’s urgent that the immigrant rights movement separates the myths about the STRIVE Act from the reality.

MYTH

The STRIVE Act would give undocumented immigrants amnesty.

REALITY

Despite the right wing’s overheated rhetoric decrying the act’s

“amnesty clause,” its architects ensured that the path to legalization

is constricted, tenuous and subject to forces beyond the control of

the immigrant population.

First, the majority of the nation’s 11-13 million undocumented people (those between ages 21 to 65, and not in the military, disabled or a single head of household) will have to leave the country within 90 days of the application process.

Second, they must pay a minimum $2,000 fine and back taxes, and show proof of presence and consistent employment before and since June 1, 2006. Current law makes those who use fraudulent documents for employment (roughly 75 percent of all current undocumented workers) inadmissible for legalization.

While the STRIVE Act would grant immigration officials the right to override this provision, it doesn’t make this mandatory. It further precludes any legalization for those convicted of a felony or three misdemeanors. These measures would undoubtedly exclude a significant portion of undocumented workers, including those who fear losing their job while undertaking the process. Many would be unable to afford lost pay and the thousands of dollars of fees and transportation and housing costs in order to “touch back” to their country of origin.

Also ineligible would be those who entered the country after the June 1 deadline, or who temporarily left the country after that period, or were unemployed (or unable to prove employment) during that period.

Ultimately, individual immigration agents, who are trained to find reasons for denial of application, would have the authority to determine compliance. Those able to satisfy the bill’s requirements would not get a green card (permanent residence). Instead, they would receive “conditional non-immigrant status,” a six-year waiting period during which time they would have to maintain consistent employment, learn fluent English and be placed in “the back of the line” behind millions of existing backlogged petitions (Waiting lists today are estimated at 5 to 7 years, although the STRIVE Act does contain clauses to expedite the process. Current law requires at least a five-year residency before attaining citizenship).

If an undocumented immigrant worker does manage to complete all steps in the STRIVE Act, she or he can become a citizen only after at least 15 years -- a fact that bill co-sponsor Jeff Flake has used as a selling point to conservatives.

While some of the undocumented could gain legal status over time, many -- perhaps millions -- would fall by the wayside.

Moreover, “conditional non-immigrant” status will make workers dependent on their jobs -- and thus more compliant with poor working conditions and lower wages, as employers could hold the threat of termination over their heads.

Coupled with the annual infusions of immigrants in a “new worker” program, the process will create a large and permanent tier of non-citizen workers bound to and dependent on employers.

MYTH

The STRIVE Act’s “new worker” program gives more protections than

traditional guest-worker programs.

REALITY

The “new worker” program in the STRIVE Act repackages the discredited

guest-worker programs of the past and present.

Under the proposal, migrant laborers could find temporary employment in the U.S. for two three-year terms. Each year, 400,000 (up to a cap of 600,000 in succeeding years) potential workers would be selected after paying a contracting fee of up to $15,000 and passing a health exam.

While these workers would be entitled to “prevailing wages,” the proposal is suspiciously vague about enforcement mechanisms to prevent employer abuse, the hallmark of previous guest-worker proposals.

Guest workers would be bound to a single employer and required to work for the duration of the contract. Any cessation of employment could be determined a breach of contract, allowing the employer to have the worker ejected from the country.

While workers would be able to leave an abusive employer, they could do so only if they can secure another job in advance with another employer, who must officially offer them work and be registered with the government to participate in the program. If a worker were to leave a worksite without notification, they would be deemed “illegal” and subject to deportation if they are not reintegrated into a registered worksite within 60 days. All temporary workers would be tracked through an “Alien Employment Management System,” so they will be identifiable if they leave a worksite.

Furthermore, the proposal doesn’t expressly guarantee the right to join a union or engage in collective bargaining. This, too, would leave workers vulnerable to employers that violate the provisions of the agreement. It is this denial of the freedom of movement and assembly, and the right to engage in genuine collective bargaining by immigrant guest workers that make this proposal so appealing for employers.

Unlike the old bracero system and current guest-worker programs, the STRIVE Act would deliver workers into virtually every sector of the economy.

Employers hope to leverage their control over guest workers to lower wages across the economy -- and to reduce the presence of unions in their worksites.

Moreover, the STRIVE Act doesn’t guarantee a path to citizenship for guest workers. They would first have to work continuously for two three-year terms to apply. They would then be required to leave the country, pay a $2,000 fee and provide evidence of a job in order to return to the U.S.

If approved, they would then receive a two-year “conditional nonimmigrant status,” during which they would have to learn fluent English and work consistently in order to petition for legal permanent residence (which could then take several more years, depending on the backlog).

MYTH

The STRIVE Act is a humane alternative to the enforcement-only

provisions of the Sensenbrenner bill.

REALITY

The text of the STRIVE Act states that the measure would “achieve

operational control of the international borders of the United

States.” In other words, both external and internal aspects of

immigration policy are to be further militarized as a precondition for

the legalization of undocumented immigrants.

The plan for external militarization includes doubling the number of Border Patrol agents (to about 24,000) by 2012, emphasizing the recruitment of former military personnel with experience in border enforcement in Iraq and Afghanistan. The bill would further add 1,200 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents to investigate “immigration crimes.”

The STRIVE Act would also provide more equipment to militarize the border--100 more helicopters, 250 additional power boats, unmanned aerial vehicles, tethered aerostat radars, cameras, sensors, satellites and radar coverage. New border control facilities would include monitoring posts, housing for agents and additional vehicle barriers.

The emphasis on militarization would extend into the U.S. The proposal includes the development of a national biometric database to track all immigrants, as well as an “Electronic Employment Verification System” to identify the undocumented. The legislation would create at least 20 new federal detention facilities with space to house at least an additional 20,000 detainees.

ICE would receive funding for 2,200 agents specifically for “workplace enforcement,” as well as computer databases for each agent, new radios, GPS systems, night-vision equipment, body armor and more patrol vehicles.

Penalties for the undocumented would also become more severe. Those who cross the border without papers will be criminalized and subject to six months in prison for a first offense; two years for a second offense, and five years for a third offense. The use of forged passports or false visas could result in 15 years in jail.

Employers would face greater sanctions, too. Those that knowingly hire an undocumented worker would be subject to a fine of $5,000 and three years in prison.

Local law enforcement would be increasingly enlisted in immigration law enforcement. The STRIVE Act would allow the federal government to “deputize” local law enforcement agencies to work with immigration agents in conducting operations in areas within 100 miles from the border and in “high impact areas” -- that is, any community across the nation where immigrants are concentrated.

The bill would also grant state governors in the Southern border regions the right to dispatch state National Guard troops to play a supporting role in border enforcement.

As if this weren’t enough, the STRIVE Act allows local police to act as de facto ICE agents, declaring that the “law enforcement personnel of a state, or a political subdivision of a state, have the inherent authority of a sovereign entity to investigate, apprehend, arrest, detain or transfer to federal custody (including the transportation across state lines to detention centers) an alien for the purpose of assisting in the enforcement of the criminal provisions of the immigration laws of the United States in the normal course of carrying out the law enforcement duties of such personnel.”

The bipartisan support for the STRIVE Act reveals how central “comprehensive immigration reform” is to Corporate America’s goal of disempowering labor in the U.S. While the Republican Party was defeated by the mass immigrant rights movement last spring, the baton has since passed to a Democratic Congress to salvage Corporate America’s vision.

For those committed to a different vision--one based on full legalization for all, democratization of society and the empowerment of working families -- the struggle continues in the streets and workplaces across the U.S.

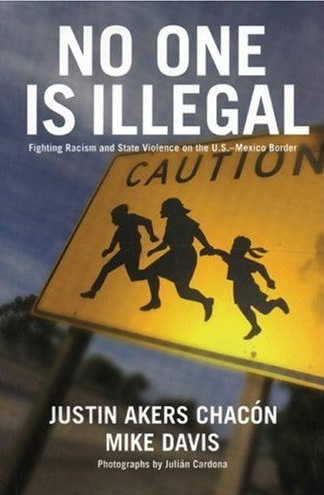

Justin Akers Chacón is coauthor with Mike Davis of No One Is Illegal: Racism and State Violence on the U.S.-Mexico Border.