In Part 1 of the World of Resistance (WoR) Report, I examined today’s global order – or disorder – through the eyes of Zbigniew Brzezinski, a former U.S. National Security Adviser and long-time influential figure in foreign policy circles. Brzezinski articulated what he refers to as humanity’s “global political awakening,” spurred by access to education, technology and communications among much of the world’s population.

Brzezinski has written and spoken extensively to elites at American and Western think tanks and journals, warning that this awakening poses the “central challenge” for the U.S. and other powerful countries, explaining that “most people know what is generally going on… in the world, and are consciously aware of global iniquities, inequalities, lack of respect, exploitation.” Mankind, Brzezinski said in a 2010 speech, “is now politically awakened and stirring.”

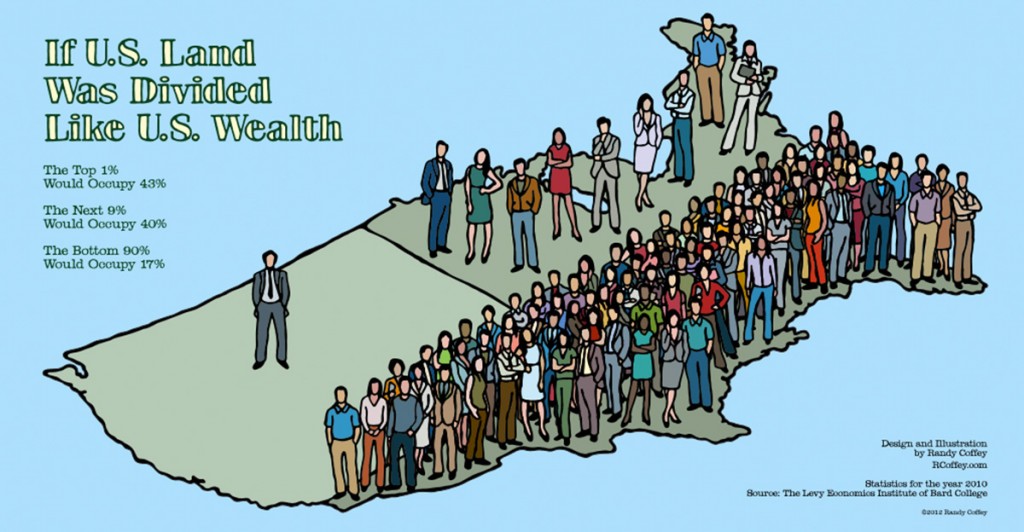

But Brzezinski is hardly the only figure warning elites and elite institutions about the characteristics and challenges of an awakened humanity. The subject of inequality – raised to the central stage by the Occupy movement – has become a fundamental feature in the global social, political and economic discussion, as people become increasingly aware of the facts underlying the stark division between the haves and have nots. While inequality is both a source and a result of the concentration of power in the hands of a few, it also represents the greatest threat to those very same power structures and interests.

As many, if not most, of us are by now aware, the global state-capitalist system is run by a relatively small handful of powerful institutions, groups and individuals who collectively control the vast majority of planetary wealth and resources. Banks, corporations, family dynasties and international financiers like the IMF and World Bank form a highly interconnected, interdependent network we now think of as the global oligarchy.

Thomas Pogge explained in the Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law that in the 20 years following the end of the Cold War, there were roughly 360 million preventable poverty-related deaths – more than all of the deaths in all of the wars of the 20th century combined. By 2004, over 1 billion people remained “chronically undernourished” and nearly a billion lacked access to clean drinking water and shelter. Roughly 1.6 billion lacked access to electricity while 218 million children were working as cheap labour.

Pogge noted that almost half of humanity – roughly 3.5 billion people – lived on less than $2.50 a day, and that all of these people could be lifted out of poverty with an expenditure $500 billion, which is roughly two-thirds of the annual U.S. Pentagon budget.

Preceding the statistics that would get popularized with the Occupy movement, Pogge asserted that the top 1% owned approximately 40% of global wealth while the bottom 60% of humanity owned less than 2%. “We are now at the point where the world is easily rich enough in aggregate to abolish all poverty,” Pogge wrote. “We are simply choosing to prioritize other ends instead.”

Still today, every year, approximately 18 million people – half of whom are children under the age of five – die from poverty-related causes, all of which are preventable. Seen through this lens, poverty, and by definition, inequality, has become the greatest purveyor of violence, death and injustice on Earth.

Meanwhile, the international charity Oxfam noted that the 100 richest people in the world made a combined 2012 fortune of $240 billion – enough to lift the world’s poorest out of poverty four times over. In the previous 20 years, the world’s richest 1% increased their income by 60%, perpetuating a system of extreme wealth which is, according to an Oxfam executive, “economically inefficient, politically corrosive, socially divisive and environmentally destructive.”

Not only that, a former chief economist for McKinsey & Company published data in 2012 for the Tax Justice Network that reported the world’s super rich had hidden between $21 and $32 trillion in offshore tax havens – a trend that has been increasing in the past three decades to reveal that inequality is “much, much worse than official statistics show.”

In early 2014, Oxfam released a report revealing that the world’s 85 richest individuals had a combined wealth equal to the collective wealth of the world’s poorest 3.5 billion people – approximately $1.7 trillion. Meanwhile, the world’s top 1% own roughly half the world’s wealth, at $110 trillion. Oxfam noted: “This massive concentration of economic resources in the hands of fewer people presents a significant threat to inclusive political and economic systems… inevitably heightening social tensions and increasing the risk of societal breakdown.”

What Does All the Inequality Mean in Terms of Instability?

Where there is great inequality, there is great injustice and where there is great injustice, there is the inevitability of instability. This relationship, between inequality and instability, has not gone unnoticed by the world’s oligarchs and plutocratic institutions. The potential for “social unrest” has gotten especially high since the onset of the global financial and economic crisis that began in 2007 and 2008.

The head of the OECD warned in 2009 that the world’s leading economies would have to take quick action to resolve the global crisis or face a “fully blown social crisis with scarring effects on the vulnerable workers and low-income households.”

The major credit ratings agency Moody’s warned back in 2009 that the growing debts among nations would “test social cohesiveness” as investors demanded countries impose still more painful austerity measures, leading to growing “political and social tension” and “social unrest.” In February of that same year, the Director-General of the World Trade Organization (WTO) warned that following the economic crisis, many nations were “going to be confronted by unrest and inter-religious and inter-ethnic conflicts.”

Brzezinski himself said: “There’s going to be growing conflict between the classes and if people are unemployed and really hurting, hell, there could even be riots.” And meanwhile, the top-ranking U.S. military official and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, commented that the global financial crisis was a greater security concern to the U.S. than either of the massive ground wars in Iraq or Afghanistan. “It’s a global crisis,” he said, and “as that impacts security issues, or feeds greater instability, I think it will impact our national security in ways that we quite haven’t figured out yet.”

Mullen’s point was reiterated by U.S. intelligence director Dennis Blair, who warned Congress that the global crisis was “the primary near-term security concern” for the U.S., adding that “the longer it takes for the recovery to begin, the greater the likelihood of serious damage to U.S. strategic interests.” Blair noted that as a result of the crisis, roughly 25% of the world’s nations had already experienced “low-level instability such as government changes.” If the crisis persisted beyond two years, Blair noted, there was a potential for “regime-threatening instability.” U.S. intelligence analysts were also fearful of a “backlash against U.S. efforts to promote free markets because the crisis was triggered by the United States.”

In November of 2008, the U.S. Army War College produced a document warning that the U.S. military must be prepared for the possibility of a “violent strategic dislocation inside the United States,” possibly caused by an “unforeseen economic collapse” and/or a “purposeful domestic resistance” and the “loss of functioning of political and legal order.” Under “extreme circumstances,” the document warned, “this might include the use of military force against hostile groups inside the United States.”

In 2009, the British spy agency MI5, along with the British Ministry of Defence, were preparing for the potential of civil unrest to explode in Britain’s streets as a result of the economic crisis, [noting] that there was a possibility the state would deploy British troops in major cities.

A December 2009 article in The Economist warned that increased unemployment and poverty along, with “exaggerated income inequalities” following the global economic crisis, made for a “brew that foments unrest.” In October of 2011, the International Labour Organization warned in a major report that the jobs crisis resulting from the global economic crisis “threatens a wave of widespread social unrest engulfing both rich and poor countries,” and pointed out that 45 of the 118 countries studied already saw rising risks of unrest, notably in the E.U., Arab world and Asia.

In June of 2013, the same ILO warned that the risks of social unrest including “strikes, work stoppages, street protests and demonstrations,” had increased in most countries around the world since the economic crisis began in 2008. The risk was “highest among the E.U.-27 countries,” it noted, with an increase from 34% in 2006-2007 to 46% in 2011-2012. The most vulnerable nations in the E.U. were listed as Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain, a fact “likely due to the policy responses to the ongoing sovereign debt crisis and their impact on people’s lives and perceptions of well-being.”

The E.U.’s “bleak economic scenario has created a fragile social environment as fewer people see opportunities for obtaining a good job and improving their standard of living,” warned the ILO, and advanced economies were “going to suffer a lost decade of jobs growth.”

An October 2013 report by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies warned that the long-term consequences of austerity policies imposed by E.U. governments “will be felt for decades even if the economy turns for the better in the near future.” The report noted: “We see quiet desperation spreading among Europeans, resulting in depression, resignation and loss of hope… Many from the middle class have spiraled down to poverty.”

The study further reported “that the rate at which unemployment figures have risen in the past 24 months alone is an indication that the crisis is deepening, with severe personal costs as a consequence, and possible unrest and extremism as a risk. Combined with increasing living costs, this is a dangerous combination.”

In November 2013, The Economist reported: “From anti-austerity movements to middle-class revolts, in rich countries and in poor, social unrest has been on the rise around the world.” While there are various triggers – from economic distress (Greece and Spain) to revolts against dictatorships (the Arab Spring) to the growing aspirations of middle class populations (Turkey and Brazil), “they share some underlying features,” the magazine reported. The common feature, it noted, “is the 2008-09 financial crisis and its aftermath,” and an especially important factor sparking unrest in recent years was “an erosion of trust in governments and institutions: a crisis of democracy.”

A sister company of The Economist, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), measured the risk of social unrest in 150 countries around the world, with an emphasis on countries with institutional and political weaknesses. The EIU noted that “recent developments have indeed revealed a deep sense of popular dissatisfaction with political elites and institutions in many emerging markets.” Indeed, the decline in trust has been accelerating across the developed world since the 1970s. The fall of Communist East European regimes in 1989 eroded that trust further, and the process sped up once again with the onset of the global financial crisis.

According to EIU estimates, roughly 43% (or 65) of the countries studied were considered to be at “high” or “very high” risk of social unrest in 2014. A further 54 countries were considered to be at “medium risk” and the remaining 31 were considered “low” or “very low.” Comparing the results to a similar study published five years previously, an additional 19 countries have been added to the “high risk” category.

Among the countries considered a “very high risk” for social unrest in 2014 were Argentina, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bosnia, Egypt, Greece, Lebanon, Nigeria, Syria, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Yemen and Zimbabwe. Among the countries in the “high risk” category were Algeria, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Iran, Jordan, Laos, Mexico, Morocco, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Turkey and Ukraine.

It doesn’t take demonstrators filling the streets to tell us that inequality breeds instability. While many factors combine under different circumstances to lead to “social unrest,” inequality is almost always a common feature. Injustice, poor governance, corruption, poverty, exploitation, repression and corrosive power structures all support and are supported by underlying conditions of inequality. And as inequality is no longer a local, national or regional phenomenon but a global one, so too is the “threat” of instability that the world’s elite financial, media and think-tank institutions are now so busy warning about. So long as inequality increases, so will instability. Resistance, and even revolution, are the new global reality.

• Read Part 1 here

• This article was originally posted at Occupy.com